H5N1 (Avian Influenza)

Report Suspected Case to DEM

Key Takeaways

- The risk in Rhode Island is low.

- As of February 2025, H5N1 influenza has been detected in Rhode Island in a noncommercial flock in January 2025 and in a noncommercial backyard flock in 2022.

- Rhode Island has smaller farms, fewer milk processing facilities, and regulations against selling raw (unpasteurized) milk.

- H5N1 influenza has been found in wild birds, dairy cattle, and commercial poultry across the country, so Rhode Island should take steps to prevent spread in the state.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and State veterinary and public health officials are working together to protect livestock, farms, and communities from H5N1. The United States has the strongest avian influenza surveillance program in the world so that the food supply remains safe. Public health officials continue to pay close attention to note any changes in the pattern of the virus and continue to prohibit the introduction of infected poultry products into the food chain.

Rhode Island is watching for H5N1 influenza by:

- Partnering with USDA and FDA to test raw (unpasteurized) milk;

- Testing wastewater for traces of the virus;

- Looking for H5N1 influenza in flu test samples that are sent to the Rhode Island State Health Laboratories;

- Performing routine active surveillance in poultry; and

- Investigating reports of sick animals.

Rhode Island’s agricultural community can play a role in keeping the risk of H5N1 influenza low by:

- Contacting the Rhode Island Department of Health for help accessing testing and treatment resources for people;

- Making sure employees are using the right personal protective equipment (PPE) based on CDC guidance;

- Wear rubber gloves, dispose of the birds in plastic bags, and call one of the numbers below to discuss disposal options for your situation. Proper composting of dead birds or on-site burial are the preferred disposal methods but may not be practicable in all cases. Proper disposal is necessary to ensure the dead birds do not serve as a source of contamination for other birds.

- Reminding employees of symptoms to watch out for (like fever, chills, body aches, cough, and red or swollen eyes); and

- Encouraging employees to get a seasonal flu vaccine

Bird owners should report sick or dying domestic poultry in their flocks to DEM by sending a report or calling 401-222-2781 or 401-222-3070 if after hours.

To report sick or dying WILD birds, please use DEM’s Division of Fish & Wildlife DEM's Reporting Form or call 401-789-0281 (weekdays, 8:30 am - 4:00 pm).

CDC has materials to help employers and employees understand how H5N1 influenza can spread and how you can protect yourselves. Please consider reading these and sharing with the people you work with.

- Toolbox Talk – Personal Protective Equipment for H5N1 Bird Flu

- Hazard Assessment Worksheet for Dairy Facilities

- New Recommendations for Protecting Yourself from H5N1 Influenza

- Order PPE in Rhode Island

- What to do if you feel sick

- How H5N1 Could Spread on a Dairy Farm

- Find a seasonal flu vaccine near you

You can follow updates about the 2024 H5N1 Outbreak at the CDC’s website.

H5N1 (also called avian influenza or bird flu) is a virus that infects wild birds (such as ducks, gulls, and shorebirds) and has caused outbreaks in dairy cattle and poultry (chickens, turkeys, ducks, and geese) facilities across the US.

Rhode Island is at risk because H5N1 has been found in hunter-harvested wild waterfowl reported along the Atlantic Flyway, which is the migratory bird route that includes Rhode Island. There is a possibility that wild birds migrating north may spread H5N1 through the flyways. This is how the virus could be spread to Rhode Island. If the disease is detected in Rhode Island in domestic poultry, affected flocks must be depopulated to prevent the spread of this highly contagious disease to additional flocks and nearby flocks will be tested to ensure that spread has not occurred.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) considers the risk to people from H5N1 infections in wild birds to be low because these viruses do not now infect humans easily, and even if a person is infected, the viruses do not spread easily to other people. Avian influenza viruses respond to standard antiviral drugs.

Press Releases

- Press Release 01-25-2025 DEM Confirms Domestic Bird Case of Avian Flu

- CDC Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Detections in Livestock

- Press Release 10-21-2022 DEM Announces RI's First Domestic Case of Avian Flu, Found in a Noncommercial Backyard Flock in Newport County

- Press Release 5-6-2022 Human Case of Avian Influenza A(H5) Virus Confirmed in the U.S., but Avian Influenza Has Not Been Detected in R.I. and Public Health Risk is Low

- Press Release 3-4-2022 State Prepares for Emergence of Highly Infectious Avian Flu That Could Have Dire Impacts on Commercial Poultry Flocks and Backyard Chickens, But Poses Low Risk to Human Health

- USDA: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

Frequently Asked Questions

Since the 2022 HPAI outbreak, there have been close to 67 HPAI detections in people (as of February 2025). Almost all have had some exposure on either an infected poultry or dairy farm. Experts at the CDC, the USDA, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are watching the outbreak carefully. For updates on H5N1 in the US, including case counts, visit the CDC web page on Avian Influenza.

The CDC considers the risk of avian influenza to be low for people. People can be infected with avian influenza viruses, but they rarely make them sick. Even if a person is infected with one of these influenza viruses, it’s hard for the virus to spread from person to person. Standard antiviral drugs, like Tamiflu, can treat avian influenza infections. View the Rhode Island Department of Health's website for more information.

Yes. Avoid unnecessary contact with live poultry or wild birds, especially those birds that appear ill. If you work directly with live poultry or wild birds, it is important to practice good hand hygiene methods washing with soap and warm water and rinsing well.

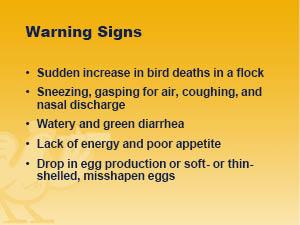

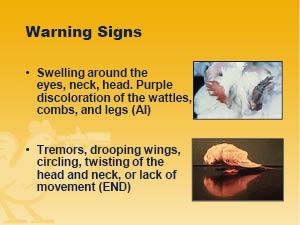

All bird owners, whether commercial producers or backyard enthusiasts, need to continue:

- Practicing good biosecurity.

- Taking precautions to reduce the chance of a disease being transported from one place to another, especially by ensuring that viruses and other germs are not carried from an infected location on clothes, shoes, vehicles, or other items.

- Preventing contact between their birds and wild birds. Direct bird-to-bird contact, whether wild bird to domestic bird, or domestic bird to another domestic bird, continues to be the main route of infection of domestic birds.

- Bird owners should report sick or dying domestic poultry in their flocks to DEM by sending a report or calling 401-222-2781 (401-222-3070, if after hours); or to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) at 508-363-2290.

To protect yourself from all flu viruses, remember to always practice good hand hygiene. Even in areas without H5N1, birds may carry other bacteria, viruses, or parasites in their droppings. You should avoid direct contact with bird droppings, if possible, and always wash your hands after contact with bird droppings or surfaces contaminated with bird droppings.

No. There have not been any cases of H5N1 infection in people acquired from Canada geese in the United States. You should teach your child to always enjoy wildlife from a distance. Not only are there viruses, bacteria (such as Salmonella), and parasites that can spread through their droppings, but approaching them interferes with their normal behavior and can cause conflict between you and them.

No. Hatching chicks in classrooms has not resulted in any human infections with H5N1. To protect against other diseases that may be spread through contact with poultry (such as salmonellosis), children should be instructed to wash their hands vigorously with soap and water after handling chicks, their cages, or food dishes.

No. Having a backyard feeder has not resulted in any human infections with H5N1. However, since the droppings of wild birds may contain other bacteria, viruses, or parasites, you should avoid exposure to bird droppings, if possible, and always wash your hands after handling your bird feeder.

Yes. There are no recommendations or prohibitions against hunting, field dressing, or eating game birds in Rhode Island. As a general precaution, hunters are always advised to wear gloves when skinning and preparing any game meat (this includes both birds and mammals) and to cook meat thoroughly before eating it. This USDA link provides guidance on dressing game birds and cooking game meat.

Yes. Most avian influenza viruses that are found in wild ducks and other waterbirds are categorized as low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI). LPAIs do not cause obvious illness in infected birds. As long as waterfowl hunters follow the basic safety rules when dressing game birds (USDA link), and game meat is cooked thoroughly (poultry should reach an internal temperature of 165°F to kill disease organisms and parasites), wild game is safe to consume.

Yes. People should never eat birds, wild or domestic, that do not appear healthy at the time they are killed whether by hunting or slaughtering them. People should never eat birds that are found dead. If domestic poultry appear healthy, they are safe to eat after being slaughtered provided they are properly cooked. Poultry products, including ground poultry, should always be cooked to at least 165 °F internal temperature as measured with a food thermometer; leftovers should be refrigerated no more than two hours after cooking. Only by using a food thermometer can one accurately determine that poultry has reached a safe minimum internal temperature of 165°F throughout the product.

Yes.

Infected birds will be prevented from entering the food chain by rapid testing, detection, quarantine, depopulation, and further testing. Infected domestic poultry typically show obvious symptoms of being sick and would not pass inspection before being slaughtered at a processing facility. The death rate of HPAI-infected chickens and turkeys is 90% or higher. Any infected birds will very likely die. Other birds in their flocks will be euthanized to contain the spread of the disease. Birds that are euthanized will be disposed of in an environmentally responsible manner so that the carcasses do not pose a source of infection to other susceptible birds. By these measures, DEM and other public health officials will prohibit the introduction of infected poultry products into the food system.

Yes. There have been no documented cases of AI virus infections in humans caused by eating properly cooked poultry products. Poultry products should always be properly handled and cooked to prevent the spread of other illnesses such as Salmonella. Egg yolks should not be runny or liquid. The cooking temperature for poultry meat should be 74°C (165°F).

For two major reasons. One, AI outbreaks can lead to devastating economic consequences for the poultry industry. Producers might experience a high level of mortality in their flocks. Thus, monitoring and controlling AI at its poultry source is essential to decreasing the virus load in susceptible avian species and the environment and safeguarding the livelihoods of poultry producers. Two, ensuring food security. One reason the Unites States has a safe food supply is because it has the strongest AI surveillance program in the world. The USDA, CDC, DEM, and RIDOH continue to pay close attention to note any changes in the pattern of the virus and to prohibit the introduction of infected poultry products into the food chain.

Avian influenza virus infections do not usually kill wild birds or songbirds. Therefore, it is extremely unlikely that any individual dead bird in RI died from an avian influenza virus infection. If it is a songbird, it is much more likely to have died from a window strike or predation by a house cat. The public is urged not to touch dead bird or dying birds. Keep pets and children away from dead birds and always wash hands if you contact a dead bird.

There are normal reasons for bird mortality. Finding a single dead bird may not be cause for alarm. A standard indicator for disease is observing several (5-10) dead birds over a short period of time at a single location. However, during times of certain disease outbreaks, such as Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), observing a single bird washed up on the beach is worth reporting.

To report sick or dying birds, please use DEM’s Bird Illness & Mortality Reporting Form.

Avian influenza viruses rarely cause disease in wild birds, and it is unlikely that any individual bird may be infected with an avian influenza virus. If you find a sick or injured animal, it is important to locate a licensed rehabilitator (click here for directory of licensed rehabilitators). Licensed rehabilitators can help you determine if an animal really needs help and if it does, may be able to provide care with the goal of appropriate release as a wild animal.

While it is highly unlikely that the dead bird may have been infected with an avian influenza virus, it is generally recommended that you not touch any dead bird, or any other wild animal, with your bare hands. Keep pets and children away from dead birds and always wash hands if you contact a dead bird. To dispose of a dead bird, use a shovel or garden tool to scoop up the dead bird and put it in a trash bag. Then place that bag into a second bag and place it in your trash. If you must use your hands to put the dead bird in a trash bag, cover them with gloves or plastic bags. After disposing of the bird, wash your hands with soap and warm water.

To report sick or dying birds, please use DEM’s Bird Illness & Mortality Reporting Form.

Please report sick, dying, or recently dead waterfowl (ducks and geese), shorebirds (sandpipers, plovers), or other waterbirds (herons) found at any location(s) to DEM’s Bird Illness & Mortality Reporting Form or call DEM’s Division of Fish & Wildlife at 401-789-0281 (weekdays, 8:30 am - 4:00 pm); or the USDA at 508-363-2290.

First, do not eat the birds. People should never eat birds, wild or domestic, that do not appear healthy at the time they are killed whether by hunting or slaughtering them. People should never eat birds that are found dead. Although HPAI does not spread from birds to people except in very rare circumstances, we recommend against handling dead birds with bare hands. In general, regardless of the cause of death, we recommend disposing of the bird by wearing personal protective equipment such as nitrile, latex, or vinyl gloves and using a shovel to place it into a trash bag for disposal in the trash. If dead backyard chickens are tested for HPAI and found to be positive, they will need to be disposed of by burial or composting. Obviously, the person handling the birds will need to immediately wash hands with warm water and soap after handling.

HPAI is highly contagious and if there is an outbreak in Rhode Island, it is likely to cause deaths in backyard flocks. We realize that in some instances, families regard their chickens as pets and their deaths will likely cause feelings of loss and grief. Please fill out this form and report any sick or dead poultry to the State Veterinarian’s Office at 401-222-2781. After hours, please call 401-222-3070.

Report sick birds or unusual bird deaths to either the RI state veterinarian at 401-222-2781 or to USDA at 508-363-2290 and please fill out this online form. If a case is suspected, the site will be immediately quarantined pending lab confirmation; and if it is confirmed, the flock depopulated within 24 hours. A control zone will may be established around the premises and movement restrictions of poultry and poultry products may be in effect. Indemnity for sick birds is available through the USDA. However, prompt reporting is essential, as indemnity will not be paid for dead birds.

H5N1 is a very contagious and deadly disease for poultry. All it takes is one infected bird, and the disease can spread from flock to flock within a matter of days. As with any highly contagious animal disease, a quick and early response is our best chance to limit the size and scope of the outbreak. Depopulating affected animals is a key part of the response. It’s one of the most effective ways to stop disease spread and protect US animal overall.

Safety attire is worn and disposed of at the affected site to ensure the virus does not spread to other farms. When an animal is suffering from an imminently fatal disease such as HPAI, emergency euthanasia or depopulation is the most humane course of treatment. All euthanasia or depopulation will be carried out in accordance with American Veterinary Medical Association guidance documents to ensure the procedures are being performed humanely.

H5N1 Detections in Dairy Herds

Since emerging in the United States in 2022, H5N1, also know as avian influenza or bird flu, has been detected in almost every state, including Rhode Island. Just as different flu viruses spread between people in different ways, so has this version of bird flu, H5N1, been spreading too. Initially restricted to wild birds and poultry, it has spilled over into mammals as diverse as wild animals such as foxes, bears, and seals; domestic animals such as cats and dogs; and farm animals such as goats and dairy cows.

On March 25, 2024, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Food and Drug Administration, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed that they had detected HPAI in unpasteurized, clinical samples of milk from sick cattle collected from two dairy farms in Kansas and another dairy farm in Texas (click here for USDA press release). Based on the findings from Texas, the flu detections appear to have been introduced by wild birds.

The public health threat is low. “Initial testing by the National Veterinary Services Laboratories has not found changes to the virus that would make it more transmissible to humans, which would indicate that the current risk to the public remains low,” the USDA states in its press release.

Resources

- NE Participating States’ Agreement Regarding the Movement of Cull Lactating Dairy Cattle

- USDA Press Release 5/10/24: USDA, HHS Announce New Actions to Reduce Impact and Spread of H5N1

- USDA Press Release 4/24/24: Federal Order Requiring Testing for and Reporting of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in Livestock

- USDA: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) Detections in Livestock

- USDA: APHIS Requirements Recommendations HPAI Livestock

- USDA: FAQs re: Federal Order to Assist with Developing a Baseline of Critical Information and Limiting the Spread of H5N1 in Dairy Cattle

- FDA Updates on Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

- CDC: Considerations and Information for Fair Exhibitors to Help Prevent Influenza

- CDC: Considerations and Information for Fair Organizers to Help Prevent Influenza

The USDA adds:

“Federal and state agencies are moving quickly to conduct additional testing for HPAI, as well as viral genome sequencing, so that we can better understand the situation, including characterization of the HPAI strain or strains associated with these detections. At this stage, there is no concern about the safety of the commercial milk supply or that this circumstance poses a risk to consumer health. Dairies are required to send only milk from healthy animals into processing for human consumption; milk from impacted animals is being diverted or destroyed so that it does not enter the food supply. In addition, pasteurization has continually proven to inactivate bacteria and viruses, like influenza, in milk. Pasteurization is required for any milk entering interstate commerce.”

In other words, the food supply remains safe. The United States has the strongest avian influenza surveillance program in the world so that the food supply remains safe. Public health officials continue to pay close attention to note any changes in the pattern of the virus and continue to prohibit the introduction of infected poultry or other products into the food chain.

For more information on this rapidly evolving situation, visit this USDA website.

Biosecurity for the Birds

Additional Resources

- USDA: Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

- Voluntary Information Form - HPAI

- USDA: HPAI Indemnity and Compensation Process

- Biosecurity Information for Bird Owners

- CDC: Considerations and Information for Fair Exhibitors to Help Prevent Influenza

- CDC: Considerations and Information for Fair Organizers to Help Prevent Influenza

- CDC: Information on Bird Flu

- CDC Avian Influenza A Virus Infections of Humans

- 2022 Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza

- USDA APHIS: Avian Influenza

- RI DEM Avian Influenza Response Plan

- USDA APHIS Avian Influenza Response Plan