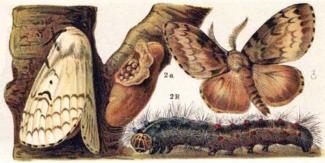

Spongy moth (Lymantria dispar) in Rhode Island

Overview

Spongy moth, Lymantria dispar, and their larvae (caterpillars) are always present in the environment. Usually unnoticed and causing little concern, their numbers are controlled by a naturally occurring virus, Nucleopolyhedrosis (NPV), and a fungus, Entomophaga maimaiga, which typically kills the majority of caterpillars before they reach adulthood.

Beginning in mid-late April and continuing through late June, the caterpillars will consume leaves of many species of broadleaf trees and shrubs – such as oaks, aspen, apple, speckled alder, basswood, gray and river birch, and willow. Less desired but still attacked are maple, black, yellow, and paper birch, cherry, cottonwood, elm, black gum, hickory, hornbeam, larch and sassafras. Older spongy moths larvae devour foliage of several species that younger larvae normally avoid, such as hemlock, and pines and spruces native to the East.

Spongy moth caterpillars avoid ash, balsam fir, butternut, black walnut, catalpa, red cedar, flowering dogwood, American holly, locust, sycamore, and yellow or tulip poplar, and shrubs such as mountain laurel, rhododendron, and arborvitae. Also consumed, but not preferred are needles of conifers – such as pines, spruces, and firs. Feeding usually occurs during night hours, but when populations are dense, caterpillars feed continuously day and night until the foliage of the host tree is stripped. They will then crawl to nearby trees in search of food.

Spongy moth numbers can increase dramatically, resulting in an “outbreak” that can cause severe defoliation of tree canopies, such as was experienced throughout Rhode Island in 2015 through 2017. While the exact cause of that outbreak was unknown, it is believed that successive years of warm, dry, spring weather was not conducive to the growth and spread of NPV or Entomophaga. This resulted in an increase in the number caterpillars surviving to adulthood (moth stage), and therefore producing a large number of eggs masses for successive generations. The significant caterpillar infestation in 2017 caused extensive tree mortality throughout the State. It wasn’t until the return of near normal rainfall in the Spring of both 2017 and 2018 that NPV and Entomophaga were once again able to gain the upper hand, causing the spongy moth population to collapse to pre-outbreak levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

The spongy moth was brought to North America from France by Mr. E. Leopold Trouvelot. His purpose was to breed hybrid silkworms that would be hardier than the Chinese species and that could be used to establish a silk industry in the United States. In 1869 some of them escaped and were apparently scattered by a windstorm. From this unfortunate start in Medford Massachusetts, spongy moths have now spread to many other portions of the United States.

In areas where they are established, spongy moths survive in low numbers in the environment, kept in check by a naturally occurring virus (Nucleopolyhedrosis virus - NPV) and a fungus, Entomophaga maimaiga. It is believed that dry spring weather slows the reproduction and spread of the fungus, allowing higher numbers of spongy moth caterpillars to reach adulthood. If that happens for a few years in a row, the spongy moth population can expand rapidly, leading to a major infestation. NPV is most effective when caterpillar densities are high, and can therefore cause the collapse of the spongyy moth population.

Somewhat true. While outbreaks are cyclic, it is only coincidence that they appear to occur in 15-year cycles. Outbreaks are unpredictable and will occur as environmental conditions allow.

There is no widespread public health threat from spongy moth caterpillars. While some people may experience the allergy-like symptoms commonly associated with contact with the caterpillar’s hairs, studies suggest that the vast majority of people’s reactions will be minor and temporary in nature, and not a general threat to public health.

The end of the outbreak is not predictable because of unpredictable future environmental conditions. Historically, outbreaks last from 3-5 years, however a few outbreaks have lasted as long as ten years.

As a rule, the State does not treat for spongy moth. A spray program can protect some foliage but will not bring about the end of an infestation.

Trees are resilient, and can survive being defoliated. Deciduous trees (those with leaves) are more likely to survive than conifers (those with needles). Other factors such as the general health of the tree, the extent and number of times a tree was defoliated, and other stressors such as drought, exposure to salt, wind, etc., play a role in whether or not a tree will survive. WE did see significant mortality from the most recent outbreak in the mid-2010s.

Egg masses can be physically scraped off the tree into a bucket of soapy water and allowed to soak overnight. Use a butter knife or putty knife. Don’t just scrape the masses to the ground as the eggs will still be viable. After the first hard freeze of fall, and up until egg hatch, egg masses can be sprayed with a 2-3% solution of dormant oil or horticultural oil. Hint: add some food coloring or dye to the mix so you can tell what you’ve already sprayed.

There are several options available to homeowners who wish to try to protect their trees. Almost all options are only suitable for individual “lawn trees” or small groups of trees whose canopies are isolated from other trees that will not be included in a treatment program.

- A homeowner can spray their foliage with over the counter pesticides containing Btk or Spinosad®. For more, view Management & Control Measures

- Hire a tree care company to spray for you. Make sure the applicator is a DEM licensed pesticide applicator and that the company is insured. Ask for proof of both. Contact Howard Cook at Howard.Cook@dem.ri.gov if you'd like to verify a license with DEM.

- Aerial spraying requires a permit from DEM Division of Agriculture and highly specialized equipment and a special type of license for the pilot. View the aerial pesticide applicator’s certificate. This method can be very expensive and the application process can be time consuming.

Tree fertilization is not recommended. Supplemental watering is much more important especially if drought conditions occur.

Tree barriers may work when caterpillar numbers are low, but only when there is a solitary tree, or small isolated group of trees. Even when installed correctly and properly maintained, tree barriers may not be able to prevent a defoliation as caterpillars can be blown long distances into a “protected” tree. If you choose to use them they are best installed just prior to the anticipated beginning of egg hatch, which varies from year to year and where you live within the state. As a very general rule, spongy moths begin to hatch sometime after April 15th. If you install tree barriers up to two weeks prior to this time you will likely stop more caterpillars but the barriers will require more frequent maintenance.

Unfortunately there is no magic answer to this question. Caterpillars can be swept or vacuumed up and disposed of in a bucket of soapy water. Caterpillar “frass” can be swept up or hosed with a garden hose or power washer.

There is no evidence that pheromone traps help protect trees during an outbreak. Pheromone traps are generally used to delimit or detect the presence or absence of spongy moths in areas either lightly infested or suspected of harboring moths, and not as an eradication method.