Earth Day

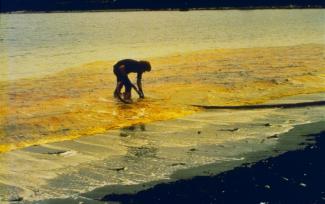

Photo: Sarah Petrarca

Think Globally, Act Locally

Since its inception in 1970, Earth Day has served as a yearly catalyst for ongoing environmental education, action and change. The first Earth Day mobilized millions of Americans for the protection of the planet. Each year, Earth Day serves as a reminder of the value of our state's precious natural resources and helps mark the progress made by Rhode Island in protecting them – from beautiful Narragansett Bay to our local waters and green spaces to the air we breathe.

Climate change, water contamination, stormwater run-off, air quality alert days, fishkills, trash, plastic pollution – these are some of the environmental issues Rhode Island and the country has grappled with recently. Yet, despite these problems, the air is cleaner than it was 50 years ago with fewer and cleaner smokestacks and our rivers don’t change color or burn anymore because of chemicals and dyes from industry.

A more sustainable world starts with all of us. While we’ve cleaned up many large sources of pollution, today many small amounts of pollution come from things like failing septic systems, run off from large parking lots, and exhaust from thousands of tail pipes. Taken together, these seemingly small sources of pollution scattered across the state, add up to big environmental problems. And, the solutions lie in the decisions that we all make each day at home, on the road, at work and at play.

More than 1 billion people in 192 countries now participate in Earth Day activities each year, making it the largest civic observance in the world. We invite Rhode Islanders to take action in their everyday lives to protect the planet. Simple things like turning off unused lights, turning off the water when you brush your teeth and recycling and properly disposing of your trash. The old adage - Think Globally, Act Locally – is a principle that many Rhode Islanders will follow this Earth Day by making small changes to help limit our impact on the environment.

Narragansett Bay is the defining feature of Rhode Island, covering 147 miles it forms the largest natural estuary in New England and sits at the heart of the state. Its riches are at once natural, recreational, aesthetic, cultural, economic, and spiritual. Residents and tourists alike depend on the coastal environment for both recreational and economical pursuits. DEM has responded to two significant oil spills in the Bay in 1989 and 1996.

On June 23, 1989, several hundred thousand gallons of fuel oil were spilled at the mouth of the Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island after the tanker MV World Prodigy ran aground on a reef near Aquidneck Island.

World Prodigy, a ship operated by Ballard Shipping under the Greek flag, was inbound to Providence when she ran aground offshore from Brenton Point State Park, after passing the wrong side of a buoy marking the channel. An estimated 300,000 gallons of oil was released into the Bay and covered close to 50 square miles. While much of the oil evaporated, the clean-up cost nearly $2 million.

After the collision, World Prodigy's captain, Iakovos Georgudis, was charged with two violations of the Clean Water Act and Ballard Shipping with one. Both the captain and company pleaded guilty; Ballard paid $1 million and Georgudis $10,000 in fines.

The North Cape oil spill took place on Friday, January 19, 1996, when the tank barge North Cape and the tug Scandia grounded off Moonstone Beach in South Kingstown, spilling an estimated 828,000 gallons of home heating oil. This spill was the worst in Rhode Island history, with oil spreading throughout a broad area of Block Island Sound and beyond, including shoreline of the Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge

More than 200 square miles of commercial fishery were closed for several months following the spill. Hundreds of oiled birds and large numbers of dead lobsters, surf clams, and sea stars were recovered in the weeks following the spill. State and federal agencies undertook considerable work to clean up the spill and restore lost fishery stocks and coastal marine habitat. The North Cape oil spill is considered a significant legal precedent in that it was the first major oil spill in the continental U.S. after the passage of the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, resulting from the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska on March 24, 1989. The law is designed to compensate the public for losses resulting from an oil spill. Over a year after the spill, the owners of the tug and paid a total of $9.5 million in criminal and other costs.

Many organizations were involved to find a solution to the disaster, and to find a way to clean up all the oil from the deep levels of the bay. DEM, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), US Fish & Wildlife service, and the United States Coast Guard, along with partners, worked together to create a restoration plan following the spill. Projects included restocking wildlife populations and protecting and enhancing their habitats. This incident and other disturbances have illustrated the need to improve both the ecological and social resilience of coastal environments.

UST Operators of today have much to thank the TV news show 60 Minutes for bringing leaking USTs to the nation's attention way back in 1984. Watch this important, if not historic broadcast to see how far we've come.

Earth Day was founded in 1970 by former Governor and Senator of Wisconsin, Gaylord Nelson. The first Earth Day in 1970 rallied over 20 million Americans from around the country and on college campuses to get involved in environmental "teach-ins". This event, which was the largest grassroots mobilization in US history, created what has come to be known as the environmental movement. It was out of this event that came the first environmental legislation - the Clean Air and Clean Water acts.

RI State Parks Tree Donation Program

Earth Day and Arbor Day are the perfect opportunities to honor a loved one, celebrate a special event, or simply give back to nature by donating a tree to one of Rhode Island’s State Parks through DEM’s Donation Tree Program. Each tree becomes a lasting tribute while supporting the health of our beautiful parks. Plantings are done twice a year, once in the spring and once in the fall. Donors can choose from Colt State Park in Bristol, Goddard Memorial State Park in Warwick, and Fort Adams State Park in Newport. For more information about donating a tree, please visit: riparks.ri.gov/donation-tree.

Rhode Island Milestones

Since 1970, efforts to improve air and water quality, clean up contaminated lands, conserve open space, increase recreational opportunities and confront climate change have greatly enhanced the quality of life for Rhode Islanders. A wide range of improvements have been made over the past five decades, including:

Air Quality

The quality of the air that we breathe has improved dramatically since the inception of the Clean Air Act in 1970 due to emissions reductions, increased automobile fuel efficiency and cleaner burning cars, power sector improvements and a shift from coal to natural gas, and stricter emissions limits for manufacturing facilities. A steady decrease in air pollutants and stricter air quality standards means less exposure and lower health risks for Rhode Islanders.

Since the enactment of the Clean Air Act just a few months after the inaugural Earth Day in 1970, emissions reductions have led to dramatic improvements in the quality of the air Rhode Islanders breathe and resulted in lowering public health risks.

Between 1990 and 2018, national concentrations of air pollutants improved 82% for lead (3-month average), 74% for carbon monoxide, 89% for sulfur dioxide (1-hour), 57% for nitrogen dioxide (annual), and 21% for ozone (8-hour). Fine particle concentrations (24-hour) improved 39% and coarse particle concentrations (24-hour) improved 26%. (Source: EPA’s Status and Trends Report – 2018)

Rhode Island’s trends resemble national trends, which are decreasing. For example, with the removal of lead from gasoline, we no longer must monitor for lead in Rhode Island. For SO2, the most recent design value is only 4% of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) standard of 75 parts per billion (ppb). Rhode Island has been in attainment of the NAAQS for carbon monoxide since 1996. We have not exceeded the NAAQS for NO2 since 1980 and the PM2.5 design values have been below the NAAQS since we began monitoring in 1999.

Air quality has improved because manufacturing and power plants became cleaner using control technologies, due to the transition from coal to natural gas, and by the adoption of cleaner-burning and more fuel-efficient cars, light trucks, and SUVs. Air quality also has improved as manufacturing in Rhode Island transitioned from pioneer sectors such as textiles, jewelry, and silverware to clean manufacturing industries that have low actual emissions per unit of output.

Although significant improvements have been made since 1970 on a national and local front, more work needs to be done. Rhode Island is within the Ozone Transport Region (OTR), which is made up of states that have specific requirements for non-attainment of ozone. The biggest issue facing OTR states is that pollution does not stop at state borders and ozone pollution remains a regional transport problem. The Ocean State is located downwind of several industrial regions and sources such as electric generation units (coal- and gas-fired) in the Midwest, Pennsylvania, and parts of the South and heavily industrialized areas in northern New Jersey, New York City, and Connecticut. Also, the corridor of I-95 is a heavily trafficked roadway that significantly adds to pollution in the Northeast. The precursor pollutants from these sources, along with ozone and fine particle plumes, are carried to RI on prevailing westerly winds. While RI is currently designated as “attainment/unclassifiable” for ozone, it is a fact that RI still exceeds the ozone standard on some days.

Another challenge is that while air quality has improved, populations that live in urban areas, near major transit corridors, or near heavily industrialized areas face a much higher pollution burden based on their zip code. Examples are neighborhoods in Providence, Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Central Falls, and other cities as well communities located near I-95, the Port of Providence, or any other significant point source emitter. The pollution caused by sources contributes to Rhode Island consistently having higher asthma rates than the United States as a whole. Around 17% of RI adults and 15.5% of RI children are diagnosed with asthma at some point in their lifetime. These are the third- and fourth-highest asthma rates in the country, according to the Rhode Island Department of Health datasets.

Rhode Island’s most urgent challenge is the same as the country’s and the world’s: reducing greenhouse gases that result in global warming. Although emissions are decreasing, more significant reductions are needed.

Here, as well as elsewhere, climate change affects air quality and air quality affects climate change. The Office of Air Resources (OAR) primarily works toward mitigating the sources of emissions that are leading to the effects of climate change. These include power plants, transportation, and the heating sector, which are the three biggest sources of greenhouse gases.

In our daily work, we oversee the sources that emit the pollutants by developing regulations, issuing permits, and conducting inspections to ensure compliance with the regulations and permits. Furthermore, each year we conduct the greenhouse gas inventory to track the GHG emissions from sources within our state and use the inventory to measure our progress. We participate in regional and national organizations and programs such as the Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management, Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, United States Climate Alliance, and low- and zero-emissions vehicles initiatives to create policies and programs that will decrease emissions.

Water Quality

Once overwhelmed by raw sewage and other pollution, today our bays, rivers, and coastal waters are cleaner and healthier as a result of strong environmental laws and significant investments to improve wastewater treatment facilities and undertake combined sewer overflow projects. In 2021, shell-fishing restrictions were lifted on portions of upper Narragansett Bay that had been in place for the past 70 years, allowing DEM to welcome shell fishermen back to historic waters.

In the 1800s, the Blackstone River Valley became the birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution, and what followed altered freshwater rivers and the Bay. Public health and aquatic life health were impacted as rivers were dammed, mills were constructed, city populations boomed, and chemicals and sanitary wastes were discharged with little to no treatment.

In the 1970s, in response to environmental degradation, major federal and state environmental laws were adopted ushering in the development and expansion of the state regulatory programs aimed at water, air, and hazardous waste. The federal Clean Water Act (CWA) was enacted in 1972, setting the attainment of “fishable and swimmable waters”. Initial efforts focused on reducing pollution from large point source discharges of wastewater, improved wastewater collection and treatment (building sewers and WWTFs) and were expanded to nonpoint sources such as cesspools/onsite sewage systems, urban and agricultural runoff.

Improvement in wastewater collection, industrial pretreatment and wastewater treatment (onsite and point sources), pollution prevent have reduced risks to public health, improved the quality of life, reduced impacts to aquatic life and contributed to the economy.

Since the 1960s the number of municipal wastewater treatment facilities (WWTFs) increased from 14 to 19 and the level of treatment has increased from 9 primary treatment facilities (settling and disinfection) and 6 secondary to 8 secondary and 11 with advanced treatment.

Industrial pretreatment dramatically reducing the amount of metals and other pollutants discharged by industries and others into public wastewater systems with a 95% reduction in the amount of Total Residual Chlorine released from all RI WWTFs compared to 1997 levels (200 versus 1,340 lbs/day) to protect aquatic life from the toxic effects of chlorine.

Rhode Island WWTFs achieved the 50% summer reduction goal required by RIGL §46-12-2(f) and RIGL §46-12-3(25) during the 2012 summer season. Between 2013 and 2016, the percent reduction of the nitrogen loads from the eleven RI and six MA WWTFs ranged from 62-73% when compared to the (pre-nitrogen reduction) early 2000s time period.

Phosphorus reductions from 6 RI municipal WWTFs RI and MA WWTFs along the Blackstone, Pawtuxet, Taunton, Ten Mile, and Woonasquatucket contributed to a 37% reduction in Baywide phosphorus loads between the early 2000s and 2013-15 (NBEP 2017). Excessive levels of phosphorus promote the growth of nuisance algae and rooted aquatic plants in freshwaters which results in reduced water clarity, poor aesthetic quality and low dissolved oxygen (DO) levels that impact aquatic life. (Pawtuxet River DO impairment and Blackstone DO and phosphorus impairments removed from 2018-2020 Section 303(d) Impaired Waters list).

- Pawtuxet River meets dissolved oxygen standards due to advanced treatment (ammonia, BOD and phosphorus reductions at the West Warwick, Warwick and Cranston WWTFs). Lower portions of the River previously devoid of oxygen meet standard of 5.0 mg/l.

- The Narragansett Bay Commission and the City of Newport have constructed facilities to capture and reduce combined sewer overflows.

- Conditional Area A closure changed from 0.5” to 1.2” of rain in 24 hours.

- Elimination of Conditional Area B in the Upper Bay (i.e. eliminating the rainfall related closure of the area for the first time in 70 years) 3,712 acres changed from conditional to approved status (bacteria impairment removed Section 303(d) Impaired Waters list).

Recognition of the need to protect groundwater came to broad public attention in RI during the early 1980s with gasoline contamination from a leaking UST affecting the Canob Park neighborhood in Richmond which was featured nationally on 60 Minutes (1983) and the detection of the pesticide Aldicarb (Temik) in private wells in across the state. The use of Temik was restricted by DEM in 1985.

Passage of the RI Groundwater Protection Act in 1985 led to the statewide mapping of aquifers and wellhead protection areas and promulgation of groundwater quality standards including a statewide classification system. Rhode Island was one of the first states in the country to have an EPA approved Wellhead Protection Program (1990) which involves activities to protect public drinking water supplies that rely on groundwater sources – over 670 wells.

DEM has collaborated with the RI Water Resources Board and water suppliers on the acquisition of lands to protect public well sites. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, various regulations governing potential sources of groundwater pollution were strengthened with provisions to prevent releases to groundwater. EPA approved primacy for DEM to implement the Underground Injection Control Program in 1984. The rules for this program were overhauled in 2010. Requirements such as engineered liners and caps for landfills, double-walled underground storage tanks, salt storage BMPs and siting restriction and setbacks have helped to reduce new incidents of groundwater pollution from industrial, commercial and other facilities. In 2017, DEM adopted groundwater protection standards for PFOA and PFAS.

With passage of the Freshwater Wetlands Protection in 1972, RI has long been a leader in wetlands protection. Regulation of alterations in and near RI wetlands have limited the loss of wetlands since that time. This is important as its estimated historic land use alterations, including filling, resulted in the loss of an estimated 37% of freshwater wetlands and 53% of salt marshes.

DEM and CRMC implement freshwater wetland regulations and have produced a variety of guidance materials to aid applicants. An Open House for the public held in 2000 attracted over 200 persons. Rules revisions in 2006 implemented many of the recommendations from a Directors Wetland Permitting Streamlining Task Force. Vernal pools were a focus of a major mapping/verification effort in the mid- 2000s. Proactive wetland habitat restoration achievements include Galilee Marsh (1997 – won Coastal American Partnership in 1999), Lonsdale Marsh (2004 – another award-winning project, and Boyd’s Marsh (2007) among other projects.

To better understand the condition of RI wetlands DEM has used EPA funding to develop and execute wetland monitoring programs beginning in 2006. This work has reinforced the need for protective buffers to protect wetland functions and values and further documented conditions in salt marshes which are highly vulnerable to climate change. Strengthening wetland protection while streamlining permit processes has been a recent focus associated with a Legislative Task Force (2013-2014) and resulting changes to state law (2015) that identified gaps in the current wetland protection regulatory scheme.

Management of stormwater - a widespread source of water pollution across RI - has evolved over time. Regulatory requirements to control stormwater runoff from new development were significantly strengthened in 2010 with release of the update Stormwater Design and Implementation Standards Manual. New requirements give emphasis to infiltration to sustaining hydrology within watersheds, low impact development concepts and “green infrastructure” – nature-based solutions. Use of such techniques to retrofit the recreational facilities at Bristol Town Beach proved effective at reducing beach closures and gained national recognition via EPA webinars, etc. Internally, DEM has consolidated permitting applications and reviews related to stormwater which are subject to state and federal rules depending on the BMPs selected. The 2019 updated Nonpoint Source Management Plan is helping guide DEM and partner actions to implement more effective stormwater management for various land uses including agricultural practices.

Management of on-site wastewater systems - DEM rules were changed in the mid to late 1990s to institute stronger soil-based siting, licensing of system designers and update design criteria. Several innovations in the OWTS program occurred during the late 1990s. A process to approve innovative and alternative system technologies was adopted in 1996. Licensing of septic designers, accompanied by new training, was instituted by rules in 1997. New soil-based siting requirements and licensing of soil evaluators followed in 1998. Protection of the coastal ponds and Narrow River estuarine waters was improved by adoption of requirements for nitrogen-reducing OWTS in 2008. Point of Sale Cesspool replacement requirements became mandated by law in 2015. The 2019 updated Nonpoint Source Management Plan is helping guide DEM and partner actions to implement more effective local Wastewater Management Districts to provide local oversight of operation and maintenance and cesspool phase out in areas where on-site disposal is the practice.

The most prevalent pollutants adversely affecting surface water quality are pathogens and nutrients. Other pollution concerns include toxics, sedimentation and the emerging concerns about personal care and pharmaceutical products. Cyanobacteria blooms (blue green algae) in freshwaters are a growing public health and management concern. Groundwater resources are most commonly impacted by nitrate and toxic compounds, including various volatile organic compounds. Addressing the pollution impacts and making stormwater and wastewater treament systems more resilient to climate change impacts.

Groundwater contamination can often persist for decades, especially in bedrock aquifers. While new releases have been significantly reduced, RI continues to be challenged by the impacts of historical releases and the cumulative impacts (densely developed areas relying on septic systems or OWTS). DEM also continues to be focused on preventing groundwater pollution including work on promoting effective agricultural BMPs and minimizing contamination due to nitrates and bacteria. Emerging contaminants, in particular, PFOA and PFAS, present a management challenge and are the focus of continuing research to better understand public health and ecological impacts. Another challenge we face in the Groundwater Protection are the implementation of advanced on-site wastewater treatment technologies and proper operation and maintenance of systems in critical areas such as drinking water supplies and surface waters.

It is a challenge to continue to permit land development in a densely populated state where opportunities for new development are limited to areas and properties that were previously un developed due to environmental constraints. Development in proximity to our wetlands and water resources is requiring new and advanced technologies and design standards for on-site waste disposal and stormwater management increasing the complexity and cost of developing. The combination of land development, forestry, agriculture, and renewable energy development have contributed to further fragmentation of wetland habitat. In RI, we see very small amount of wetland losses year to year thanks to the strength of the Freshwater Wetland Regulations and the dedicated permitting staff however there continue to be impacts to wetland buffers across the State. The biggest challenges we face today are the strengthening our Freshwater Regulations to reflect available science regarding wetland buffer protection and the responsible permitting of renewable energy projects such as solar farms, hydro electric generation, and wind energy.

The local capacity to plan for and fund the retrofitting of stormwater infrastructure remains a major challenge. DEM is working with EPA and partners including the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank (RIIB) to build capacity through training, technical assistance, etc.

Without resiliency adaptation, the increased rainfall intensity and re-occurrence of large precipitation events will likely overwhelm and damage stormwater and wastewater conveyance and treatment systems leading to increased discharges of pollutants and risks to public health and aquatic life.

Climate change is changing the way we design for flood control and stormwater management. Precipitation data used for engineering to design drainage, culverts, and stormwater management systems is evolving. State building and permitting design standards need to be updated to reflect this. Increased frequency of flooding has made management of flood plains more complex and critical. Increases in localized flooding have increased public complaints and the need for better coordination between State and local permitting.

Climate change has brought attention to the fact the Freshwater Wetlands serve a very important part in Climate change resiliency. By maintaining and restoring our natural systems (e.g floodplain and wetlands) on a watershed basis we not only protect one of the biggest carbon sinks in the natural environment (e.g. wetlands) but we also protect and enhance natures ability to absorb, retain, filter and treat precipitation in a sustainable way.

Sea level rise that causes rising groundwater and increased saltwater intrusion in the coastal areas has made the protection of groundwater drinking water supplies very challenging. Existing on-site wastewater disposal systems are being effected by rising groundwater effecting the treatment provided. Siting new systems in these areas for new or expanded development is not sustainable in sensitive areas.

Land Revitalization

The remediation and redevelopment of brownfields – vestiges of Rhode Island’s industrial past as the birthplace of America’s Industrial Revolution – has mitigated the threat to public health and the environment from exposure to uncontrolled contamination. Since the establishment of the federal brownfields program in 1994, RI has received almost $46.6 million in federal Brownfields support for cleanup work, job training, program support and site assessment work. On October 1, 2021, the Targeted Brownfield Assessment Program received $300,000 from EPA to do environmental Assessment work throughout the State. In 2014, $5 million in state brownfields cleanup funding resulted in the cleanup of 21 sites spanning 126 acres. An additional $9 million in Green Economy Bond funding (2016 - $5 million, 2018 - $4 million) through DEM’s Brownfields Remediation and Economic Development Fund has since been able to supply funding for an additional 42 projects in communities across Rhode Island, helping build new schools, businesses, affordable housing and green energy projects throughout the state. Since the first Earth Day in 1970, DEM’s efforts and these clean ups have also helped revitalize areas such as Quonset and Newport. Transforming abandoned former naval facilities and wastelands into state-of-the-art engines of economic growth for the State. These efforts to address the remnants of our industrial past, have helped revitalize our State, creating more vibrant and livable communities, while also preserving many of the historic mills that make Rhode Island truly unique.

In the 1970s, there were no regulations of underground storage tanks (USTs) or gas stations. In the early 1980s, that changed when 60 Minutes aired a segment titled "Check Your Water" that highlighted the plight of residents of the Canob Park neighborhood of Richmond, Rhode Island. These neighbors were forced to buy drinking water and travel to relatives’ houses to take showers because their groundwater wells had been contaminated by gasoline leaking from underground storage tanks at a nearby gas station.

This 60 Minutes segment, along with similar stories about the effects of underground contamination across the nation, galvanized support for Congress to enact amendments to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) to include the regulation of gasoline and underground storage tanks. In the decades following, more leaking tanks would be discovered at gas stations, the most severe cases including Coffey’s in Newport, Willie’s Texaco in East Greenwich, and Duva’s in Providence. The highest profile of these incidents, which again garnered national attention, was the North Main Street Mobil release in Pascoag. The subsequent contamination knocked out the village’s only public drinking water supply and affected more than 5,000 Rhode Islanders in September 2001. Today USTs are heavily regulated operations, most with double-walled systems to ensure against the kind of catastrophic leaks just described.

The open burning of garbage, routine dumping along the Blackstone River, and chemical dumping of out-of-state wastes were commonplace in Rhode Island in the 1970s. Recycling didn’t exist! That changed in 1980 with the passage of the federal RCRA and Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), better known as the Superfund law. The most hazardous of the waste disposal sites became RI’s earlies Superfund Sites. These included the Picillo Pig Farm in Coventry, the Landfill and Resource Recovery site operated by the Wilson brothers in North Smithfield, the Davis liquid waste site in Smithfield operated by Billy Davis, and Western Sand and Gravel in Burrillville. All were listed as Superfund Sites in 1983. The Central Landfill in Johnston, purchased by the State from the Silvestri Brothers, was added to the Superfund list in 1986.

In the years following, stricter and stricter requirements were developed to separate hazardous from solid waste, then medical waste from solid waste. The “trash crisis” in the mid-1980s resulted in RI becoming a national leader in recycling with passage of the Rhode Island Recycling Act in 1986. This was the first statewide, mandatory recycling law in the country. Additional milestones of environmental protection included the promulgation of revised landfill regulations in 1992 requiring new landfills to be engineered with double lining and impermeable caps, like the later phases of the Central Landfill, and promulgation of separate rules governing medical waste management. Separate medical waste rules were developed after national news coverage in the early 1990s regarding used hypodermic needles and other medical waste washing ashore on RI state beaches, largely from ocean dumping still being conducted out of New York City.

Rhode Island, a small state known for its fresh produce, dairy farms, and seafood, is making strides in food waste diversion. There are two types of food waste – Excess Food and Wasted Food. Although these two terms sound similar, their solutions are drastically different. Excess food, when occurring in large enough quantities, should be collected, and donated to the members of the greater than 54K RI households who are food insecure. Wasted food, or food that is no longer edible, can be used for agricultural feed, anaerobic digestion, or composting. All of these choices will prevent food from breaking down in the landfill where it would emit dangerous greenhouse gases. In 2014 RI passed a Food Waste Ban with the objective of diverting food waste from the landfill. This ban has been amended since that time to cover more generators and educational intuitions. To reach the goals of the Food Waste Ban, The Department has partnered with local stakeholders to meet this challenge.

The state program that incentivizes the redevelopment and productive use of polluted sites – known as brownfields – came into being by regulation in 1993. It was an offshoot of the Superfund program and RCRA hazardous waste program designed to get contaminated sites cleaned up faster and more effectively. In 2002, federal legislation sponsored by US Senator Lincoln Chafee was passed into law authorizing significant new federal funding to states. Since that time, RI applicants (not just DEM) have received almost $47 million in federal brownfields support, of which nearly $11 million has gone directly to cleanup, almost $1.1 million going to job training, $19 million to DEM program support, and $7.3 million going to site assessment work.

The 2014 ballot included a $5 million brownfields bond – the state’s first such bond. Voters approved the measure. Another $5 million brownfields bond was passed by voters in 2016, and a third installment of $4 million was included on the 2018 ballot. Since 2018, DEM has supported Rhode Island's commitment to clean energy by significantly increasing the emphasis on the green energy reuse option in the scoring criteria for brownfields funding request for proposals. This has resulted in DEM selecting projects that have become solar farms, featured rooftop solar arrays, or transformed decrepit landscapes into urban flower farms and LEED-certified apartment buildings. Slightly over half of the $14 million in State brownfields funding has been awarded to projects located in Environmental Justice areas, transforming blighted properties into much needed affordable housing and recreational spaces.

Since its inception in 1993, the DEM Brownfields Program has capitalized dozens of transformational projects across Rhode Island. Brownfields grants have unlocked more than $948 million in other investment and supported around thousands of jobs, and cleaned up over 7,360 acres of contaminated brownfields. Half of State funding has developed projects in Environmental Justice areas. These projects have helped build new schools, businesses, affordable housing, and recreational space on formerly vacant properties throughout the state.

The US Environmental Protection Agency bestows The Phoenix Award for excellence in brownfield redevelopment. RI has had three winners:

- 2003 – Thames Street Landing in Bristol

- 2005 – Save the Bay headquarters in Providence

- 2011 – Woonsocket Middle School

Other notable brownfield redevelopment success stories include the Citizens Bank headquarters in Johnston, the Westerly Education Center, Farm Fresh RI and Meeting Street School in Providence, and Macomber Stadium in Central Falls; as well as the on-going Tidewater Landing project in Pawtucket, and Kettle Point in East Providence!

For DEM’s UST Program, it’s ensuring the continued maintenance and proper operation of the advanced double-walled tank systems that replaced their earlier predecessors, and eliminating the few remaining single-walled systems that have been grandfathered in.

The most difficult challenge facing the Solid Waste and Recycling Program continues to be something almost entirely out of its control: the “throwaway culture” that pervades American life. Solid waste management is a universal issue that matters, or should matter, to everyone – yet ensuring fair and effective solid waste management, including robust recycling programs with high adherence rates, is very hard. DEM continues to strive for a more sustainable waste management model over the existing consumption / disposal model. Related challenges include proper recycling, particularly of construction and demolition (C&D) waste stream, and effectively separating / composting food wastes. The Program also continues to push sustainability thru a variety of "Producer Responsibility" measures for electronics, food waste, and others.

Funding uncertainty stemming from the COVID-19 public health crisis might rank as the biggest challenge facing the DEM Brownfields Program. With its industrial legacy, Rhode Island has many polluted sites that could be repurposed to transform neighborhoods and benefit great numbers of people, but only limited funds remain. The Brownfields Program is the classic win-win, for both environment and economic benefits. Historical preservation also is a winner on many of the projects, where mills and industrial heritage are revitalized and repurposed to meet community needs.

The relationship between climate change and solid waste management is circular. The production of goods and subsequent waste contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, pollution, and general environmental degradation — in some cases drastically. By increasing our national recycling rate and cutting the amount of waste we generate by nominal percentages, we could slash emissions by tens of millions of metric tons of carbon equivalent. The process of extracting resources such as trees and minerals both depletes the resources and releases GHGs. The transportation of goods and materials throughout the stages of a product’s lifecycle – from extraction of materials to manufacture of the product to shipping finished goods to retailers / consumers and ultimately to transporting litter (especially packaging) to the landfill or recycling facilities – uses resources and releases GHGs. And finally, as some materials degrade in the anaerobic environment of a landfill, methane is released. Methane is a potent GHG, with as high as 84 times the impact on warming the climate than CO2.

The best approach is to prevent the need for disposal in the first place by reducing, reusing, and recreating products. Instead of destroying the materials, this mitigates climate impacts upstream. Working toward a much more sustainable materials management model versus merely the management of waste disposal – shrinking the carbon footprint of America’s consumer culture – is the crucial step that must be taken.

On the other hand, brownfields redevelopment is a hopeful key to revitalizing our urban centers and creating more livable environments for our citizens while also reducing GHGs. Applying “smart growth” land-use concepts and using clean transportation systems can mean saving more trees, forestland, open space, and reducing the negative impacts of commuting.

Sustainable Fisheries

Effective fisheries management measures have improved the stock sizes and status, such as for the Atlantic striped bass and sea scallop fisheries. In the 1970s and 1980s, the striped bass population crashed due to overfishing and environmental issues. The collective effort of states to reduce harvest, and in some states initiate moratoriums, allowed for the population to rebuild by the late 1990s. This success story had a positive impact on both commercial and recreational fishing through the 2000s. Atlantic sea scallops also experienced a similar story around the same time frame. Similarly, Atlantic sea scallops were declared overfished in 1997. By using a suite of management tools thereafter – including closed areas, effort reduction, gear and crew restrictions – led to rebuilding the population by 2001. The rebuilding of sea scallops has been extremely important for southern New England coastal communities, including New Bedford and Point Judith, as sea scallops are one of, if not the largest, landed species in these ports.

Over the last few decades, there have been multiple success stories of effective fisheries management measures improving stock sizes and statuses. One of these cases is Atlantic Striped bass in the 1990s. In the 1970s and 1980s, the striped bass population crashed due to overfishing and environmental issues. The collective effort of states to reduce harvest, and in some states initiate moratoriums, allowed for the population to rebuild by the late 1990s. This success story had a positive impact on both commercial and recreational fishing through the 2000s. Bluefish similarly were deemed to be at concerning population levels in the late 1990s, but after a nine-year fisheries management rebuilding plan, the stock was deemed rebuilt.

Atlantic sea scallops also experienced a similar story around the same time frame. Sea scallops were declared overfished in 1997 but using a suite of management tools thereafter – including closed areas, effort reduction, gear and crew restrictions – led to rebuilding the population by 2001. The rebuilding of sea scallops has been extremely important for southern New England coastal communities, including New Bedford and Point Judith, as sea scallops are one of, if not the largest, and the most valuabe species landed in these ports.

Recent success has been seen for several groundfish species as well, with many of their overfished or overfishing is occurring statues recently changed. These success stories highlight how fisheries management can be successful but does not suggest that rebuilding species results in sustained success. Striped bass represents an example of such a case, as the stock is currently overfished. Agencies must continue to evaluate management options that optimize sustainable harvest under changing ecosystems and that also strive to reduce the logistical hurdles for the industry.

The movement of many Mid-Atlantic species north in recent years as a result from climate change has led to these species being more plentiful in the Rhode Island region and accessible to commercial and recreational fishers. However, the quota management for these species has been largely unchanged, with the species distribution and quota allocation for states incongruous. This discrepancy has made the management and quota allocation amongst the Atlantic states extremely challenging and in need of modernization. As an example, most of the black sea bass quota is situated in the southern states, but a large segment of the population now resides in southern New England. The historical or static quota allocation with increased presence and interactions with northern states has led to Rhode Island fishermen to experience frequent closures in this fishery coupled with high rates of regulatory discards. This situation is damaging to our marine fisheries management system, and results in high discard mortality rates that could be avoided with appropriate quota allocation. While recent minor advancements have been made to restructure the management structures to address this issues, much more work is needed.

Another challenge we face is working to create more flexibility for commercial and recreational harvesters. Dynamic changes in fisheries management, often in response to changes in fish population sizes and access to the resource due to a suite of factors (e.g. climate change, harvest pressure, endangered species protection, renewable energy development), as well as a changing economy, makes it challenging for many fishers to make a living via seafood harvest. For many of these businesses to be sustainable, they must have a high degree of flexibility in order to take advantage of changes in quotas, market prices, weather-permitting sea days, and more. Many fisheries management plans are specific to individual fisheries and are restricted based on reporting and enforcement logistics. We have and continue to work toward building programs that increase economic opportunities, improve safety, reduce carbon footprints, remain enforceable, and most importantly, ensure sustainable fish populations. The winter fluke aggregate program, multi-state possession limit, and weekly summer flounder and black sea bass pilot aggregate program are all management efforts RIDEM has taken toward this effort. Additional initiatives that acknowledge sector or fishing differences, such as creating a standalone party-and-charter management regime, will continue to be priorities for the Division.

Perhaps the greatest challenge fisheries management has faced in recent times is managing fisheries in response to other new stressors. Changes in climate (see below), right whale population declines, and marine spatial planning endeavors have posed additional challenges to managing fisheries, all of which can have negative consequences on or may compete with fish harvest. As marine fish and invertebrate populations are negatively influenced by climate change (via warming waters, increased disease prevalence, ocean acidification, increased predation pressure, etc.) decline, there are few management measures available to counteract climate change directly, and often result in the need to reduce fishing effort to mitigate these effects. Not only does that leave harvesters bearing the burden of rebuilding the stocks despite these declines attributed to other sources, but it makes it challenging to predict with certainty that reducing harvest will combat these forces of climate on fish stocks. While preserving right whale populations is of critical importance to our nation, it will certainly have major impacts to commercial fishing industries and local economies. Thus, mitigating these adverse impacts to the fishing industry while making meaningful management measures to help improve right whale populations poses many challenges. Similarly, moving towards renewable energy alternatives is paramount for curtailing climate change, but we must do so carefully to minimize conflicts with other users of development areas (including commercial fishers) and prospective impacts it could have on marine species. Wind farm development has the potential to displace significant portions of the fishing industry, jeopardizing jobs and reducing local economies. As such, this new initiative for offshore wind development has required a great deal of new fisheries management work, including analytics, stakeholder engagement, and changes to regulation, to ensure successful coexistence of these entities.

Climate change has had pronounced impacts on the Rhode Island marine fish community. Fish abundance in our region has largely moved from a bottom dwelling species composition, such as winter flounder and American lobster, to species that live higher in the water column like butterfish. The latter species were much more common in the Mid-Atlantic than in RI waters 25 years ago but have now become residents of our waters. Species like winter flounder have declined by 98% in the last 30 years, and require creative, proactive management to sustain the remaining population.

Climate can influence species through several factors, including changes in ocean chemistry, currents, and ecosystem (e.g., predator-prey) dynamics. The largest climate change factor for these fish community shifts has been from water temperature. Warming waters of southern New England, including Narragansett Bay, have made the region unsuitable for many species that historically have resided within the area. For example, American lobster once inhabited various regions throughout the Bay, but with warming waters, this iconic species only resides in the colder, deeper waters of Narragansett Bay, and in deeper offshore waters. Species like black sea bass, striped sea robin and squid, which were far more common off the coasts of Virginia and North Carolina, are now more numerous in Rhode Island waters. With this species composition change has come the need for the fishing industry to adapt to the new environment. Not only has the target catch of Rhode Island harvesters changed, but these fishers now need to diversify their target species to make them more adaptable to future changes in species composition and abundance due to climate change. The Jonah crab fishery provides one example of this adaptability. For many years Jonah crab was simply a bycatch species in the American lobster fishery. However, with the decline in the American lobster stock (due to climate change) and increase in market price for crab meat, Jonah crab became a directed fishery that now supports many Rhode Island fishers, with Rhode Island being the second largest landing state of the Atlantic U.S. The ability for the lobster fishery to pivot to harvesting Jonah crab using their existing infrastructure (including traps, boat configuration, and expertise on the species) has allowed many of these businesses to continue operating.

Land Conservation

Almost 50,000 acres of land have been protected and we’ve invested almost $85 million in grants for more than 541 recreation projects in all 39 Rhode Island communities and awarded funds to municipalities and local non-profits to support trail development throughout the state.

Since 1970 DEM has protected almost 50,000 acres of land and invested over $50 million in Open Space Grants to municipalities, land trusts, and non-profit groups. DEM has partnered with The Nature Conservancy, The Audubon Society of Rhode Island, and dozens of land trusts and towns to protect land in all 39 municipalities – invaluable open space and agricultural land that cleans our air and water, provides recreational opportunities for all Rhode Islanders, and land to grow our food – as well as providing critical habitat and refuge for our wildlife. This includes protection of iconic places like Rocky Point in Warwick and Tillinghast Pond in West Greenwich, as well as dozens of open spaces enjoyed by people and wildlife alike.

By Decade:

- 1980: 5,482 acres

- 1990: 10,332 acres

- 2000: 8,538 acres

- 2010: 17,175 acres

- 2020: 8,159 acres

RI has also strongly supported development of recreational sites. In the past 30+ years, nearly $85 million in recreation grants has been awarded to more than 541 projects. These projects include playgrounds as well as stabilizing natural features and enhancing ecological habitats. Additionally, funds have been awarded to communities and local non-profits to support trail development throughout the state.

Land preservation programs are largely funded by State voter approved bond funds leveraged with grants from various Federal programs, and non-profit or local organizations. Grants are awarded through matched funding from communities and can be challenging for fiscally stressed budgets that may not have extra funding even for highly valued conservation efforts.

Farmland preservation efforts experience some different challenges. This is a highly complex program that has seen success protection the first generation of farms. As those farms begin the process of transferring to the next generation, however, ensuring that protected farmland remains in the hands of farmers will be our next big challenge.

The process of protecting property (appraisals, title reports, securing funding) is challenging for property owners who may be weighing offers from private developers. Rhode Islanders have consistently provided funding to protect land and provide recreational opportunities – but there are many wonderful sites that we were unable to preserve in the face of fast-moving private sales.

DEM’s Land Conservation and Acquisition Program incorporates climate change impact planning into its project considerations. For example, when prioritizing land for protection, the following are considered:

- Will this project help species migrate as habitats change in a warming climate?

- How will sea level rise impact this project?

- Will this project conserve our valuable forests, which provide carbon sequestration?

DEM works to conserve sensitive wildlife habitats and species, preserve forest health, increase the amount of food produced in the state, and provide outdoor recreational opportunities, all while balancing competing demands and addressing the significant threat of rising seas and a changing climate.

DEM conserves land using numerous strategies, such as:

- Acquire large, forested parcels that add acreage to existing management areas, that facilitate connectivity of habitats, that sequester carbon, and that create new conserved core forests of 500 acres or more. Acquire smaller, targeted parcels that can support critical habitat, such as riparian areas.

- Purchase open land/existing fields not suitable for commercial agriculture, or lands where the creation of grassland and shrubland habitats would benefit at-risk species, and manage those fields for habitat and hunting opportunities.

- Facilitate climate change mitigation by pursuing strategic coastal and riverine acquisitions, including adjacent upland areas, for salt marsh migration opportunities.

- Purchase land for recreational use: open space for hunting, fishing, and trail use; single points of access to water; and parcels for developed recreation such as swimming and camping.

- Purchase economically viable farmland for affordable transfer or lease to farmers.

- Support special projects, eg. purchasing land for DEM facilities to migrate inland.

Rhode Island is a small, dense state with significant development pressure, and tremendous use pressure. DEM purses a strategic approach that acknowledges a “best” use for each acquisition so as to ensure that all the goals of the Land Conservation and Acquisition Program are fulfilled.

Wildlife & Habitat Restoration

Rhode Island has seen a remarkable recovery of many imperiled bird and wildlife species such as the wood duck, wild turkey, snowy egret and bald eagle since the 1970s. Fish passage restoration projects including dam removals, traditional fishways, and nature-like fishways on rivers throughout the state have increased spawning and nursery habitat for migratory fish and benefited our freshwater fisheries.

Dams and their impoundments disrupt river habitat connectivity and restricts the movement of migratory and resident fish. With the passing of the Anadromous Fish Conservation Act in 1965, fish ladders were constructed on many of RI’s rivers throughout the 1970’s. The Act authorizes federal grants to the states or other non-Federal entities to improve spawning areas, install fishways, construction fish protection devices and hatcheries, conduct research to improve management, and otherwise increase anadromous fish resources.

Fish ladders, or fishways can be used to bypass blockages; this is the most commonly applied solution to restoring fish passage over impediments in Rhode Island. Throughout the 80’s and 90’s there was limited fish passage work outside of the operation and maintenance of the previously constructed facilities. In recent years, DEM has partnered on numerous fish passage projects including dam removals, traditional fishways, and nature-like fishways on rivers throughout the state opening thousands of acres of spawning habitat for migratory fish and hundreds of river miles for river connectivity between the marine and freshwaters. The rapid advancement and expertise in fisheries science and telemetry allows scientists to track migratory fish and evaluate fish passage efficiency and fish migration delays. In addition, DEM has begun working with project partners to improve older existing fishways which were built over 50 years ago. Examples of improvements include the recently completed modifications to the Echo Lake fishway on Mussachuck Creek in Barrington and last years improvements at the Hamilton and Belleville fishways on the Annaquatucket River.

Through completion of five major dam removal and river restoration projects within the last 10 years, the headwaters of the Pawcatuck River are once again open to spawning of migratory fish, for the first time since colonial and later development of numerous mills and dams along this river.

These projects were completed through the investment of more than $10 million of federal, state and local funding and the energetic leadership of the Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association (WPWA) and The Nature Conservancy, with funding and technical support from DEM, U.S Fish & Wildlife Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Geological Survey, the RI Coastal Resources Management Council , Save the Bay, the towns of Richmond, Charlestown, Hopkinton and Westerly in Rhode Island and Stonington in Connecticut, as well as numerous landowners and citizens from these communities. Partners continue to look at the best fish passage improvement options for Cronan Landing and the Potter Hill fishway on the Pawcatuck River. Fish monitoring has continued on the Pawcatuck River and DFW has partnered with USFWS to install video monitoring of returning migratory fish on the lower sections of river.

Beyond the benefits to migratory fisheries by opening new spawning grounds and providing much improved passage in place of outdated fish ladders, these projects have significantly reduced flood risks for these communities that have been hard-hit by several massive flood events within the last 15 years, by both lowering the profile of the river and removing the risk of dam failure and release of impoundments to downstream areas. These projects also resulted in significant recreational benefits to residents and visitors to Rhode Island, providing safe boating passage through sites that had previously required portaging, as well as improving river continuity for all aquatic species to the benefit of those who enjoy fishing on the river.

Prior to 1970, species such as wild turkey were essentially eliminated from many of their native areas. The remarkable recovery of numerous previously imperiled bird species in Rhode Island like the wood duck, wild turkey, snowy egret, and bald eagle is deeply interconnected with the legacies of America’s conservation funding distributed to state wildlife agencies from the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (Pittman-Robertson Act). This funding generates revenue for fish and wildlife conservation programs through excise taxes firearms and ammunition and fishing and hunting licenses and permit sales. These programs have funded numerous habitat projects enabling at risk species to recover. Early successional habitat, in decline since wide scale farm abandonment after WWII, has been the focus in recent years with the intent of benefiting a variety of species including the New England cottontail, our only native rabbit, and American woodcock.

Through this funding and the hard work of the Division, birds such as the wild turkey are thriving today. Other species such as white-tailed deer and wood duck have flourished due to adaptive harvest and habitat management. Habitat projects involving this funding in cooperation with partners like The Nature Conservancy and Ducks Unlimited have led to the development of wetlands that benefit all species of migratory waterfowl, reptiles, and amphibians. The rapid advancement and expertise in wildlife science and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has also allowed for greater precision across time and space in management of species as well as a deeper understanding of complexity in reasons for declines. Incorporating this expertise into management plans for modern forestry practices and the use of prescribed burning has expanded the capability of conserving sensitive habitats in addition to creating new ones. Our understanding of habitat and species management and the ever-changing landscape continues to improve.

In these decades, several islands in Narragansett Bay have been transferred to DEM ownership and are now managed for wildlife. They host some of the prolific nesting areas for herons, egrets, and American oystercatchers, as well as nesting and migration stopover sites for songbirds.

Without limited federal funding received from the Section 6 of the Endangered Species Act and initiative by the Division of Fish & Wildlife, American Burying Beetle would in all likelihood be extinct from RI, the only robust and sustainable population east of the Mississippi (though Nantucket began a reintroduction program in 1994, Ohio also has an experimental population).

DEM’s Division of Fish and Wildlife supports a long tradition of fishing, hunting, and outdoor recreation funded through fishing and hunting license fees matched by federal dollars. Engagement in shooting sports has increased resulting increased federal funding to states, via the Wildlife Restoration Program. Participation in fishing and hunting in Rhode Island has declined since the 1980s, resulting in decreased license and permit sales and consequently less revenue for the Division to leverage federal funds used to perform important wildlife and habitat conservation activities.

For DEM’s Freshwater Fisheries, it’s the increase of water temperatures from climate change affecting the composition of fish species throughout Rhode Island from cold water habitats to warm water habitats. In our rivers and streams, wild brook trout habitat is affected by water temperature fluctuations, development, dams and culverts which impede populations movements, and protection .

Statewide, invasive aquatic plants have increased in our streams, lakes and ponds as a result of warming temperatures, a prolonged drought season, residential and agricultural nutrient runoff and infestations from outside sources. This has resulted in native plants being choked out and a decrease in habitats for native fish, amphibians, reptiles, invertebrates and waterfowl. Toxic algae infestations of Cyanobacteria or blue-green algae have increased both in scope and duration impacting the health and safety of recreational boating and fishing constituents. These issues have mandated mitigation efforts of repeated mechanical and chemical freshwater treatments.

Accelerated habitat loss or conversion has also resulted in extensive deforestation and fragmentation of existing tracts of contiguous forested habitat in the state. Loss of habitat can threaten wildlife species, particularly interior forest species that are sensitive to disturbance and changes in habitat continuity, and lead to a direct loss of available food, shelter, and breeding habitat. Urban sprawl exacerbates these problems leading to continued fragmentation of larger tracts and disturbance of valuable core habitat areas.

Climate change has caused changes in the recurrance of wildlife migrations and loss of habitat. Warming temperatures have impacted shifts in the distribution and composition of plant and animal species, as well as habitat types, and caused potential habitat degradation from the spread of invasive species.

Warming waters have caused a transition in diadromous fish species returning to RI freshwaters. Atlantic salmon and smelt have declined over time, and in recent years there has been an increase of the blueback herring to alewife in the river herring composition. Fish monitoring results also show an increase in gizzard shad as their range moves north. Diadromous fish migrations have started earlier during the spring in recent years.

Climate change may bring sweeping ecological consequences to Rhode Island and we can expect that our amphibians and reptiles will be impacted in a big way. Amphibians (like frogs and salamanders) and reptiles (like snakes and turtles) are particularly sensitive to changes in their environment because they are ectotherms - their body temperature mirrors the temperature of the air, substrate, or water surrounding them. Reptiles and amphibians in Rhode Island and around the globe are already facing daunting conservation challenges from impacts like habitat loss, disease, and illegal collection. The unprecedented rapid shifts in climate and sea-level rise may only stress populations further, bringing them closer to the brink.

Sea level rise is of particular concern to one native Rhode Island turtle - the diamondback terrapin. Terrapins live along the Rhode Island coast in salt marshes and the brackish waters surrounding them. Salt marshes are critical habitat for terrapins serving as a place for foraging and over-wintering. Sea-level rise is already resulting in a rapid loss of salt marsh habitat in Rhode Island and the impacts to terrapins could be severe if no action is taken. This will also negatively impact Atlantic Coast flagship bird species such as Salt Marsh Sparrow and American Black Duck, that depend on salt marsh habitat throughout much of their life cycle.

RIDEM, in partnership with many partner organizations, is committed to mitigating the effects of climate change and to preserving native wildlife through protection of critical habitat, protection of clean air and water, law enforcement, environmental education, and a commitment to clean energy.